Like with all kinds of mediums, Bara has a history of its own. And it comes with its own prejudice. History for some reason won’t always tell the full story despite the amount of information today.

Bara (薔薇) in itself translates into “rose”, a flower most of you are familiar with. If you don’t understand why, the flower is effeminate in symbolism and it is used a lot in Shoujo series when any characters experience a form of excitement. Men being effeminate was taboo and most figures are closeted due to fear of being disowned and or being exposed in a bad light. Back then it was seen as a derogatory label until a shift came in Japan of the 1960s.

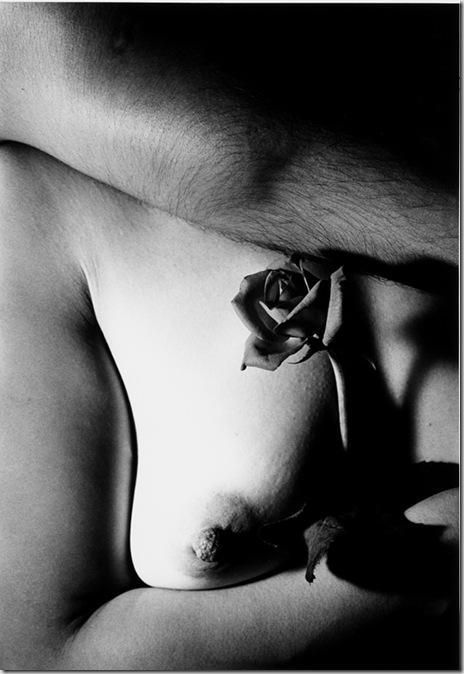

Two men, namely Yukio Mishima and photographer Eikoh Hosoe teamed up for a semi-nude photoshoot with Yukio donning a loincloth, exposing his bare muscles. Yukio even gave consent to Eikoh to do what he pleases, which became the start of gay media in a highly conservative Asian country until the first commercially successful gay magazine started circulating. A sample of the photos are compiled into an anthology called Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses.

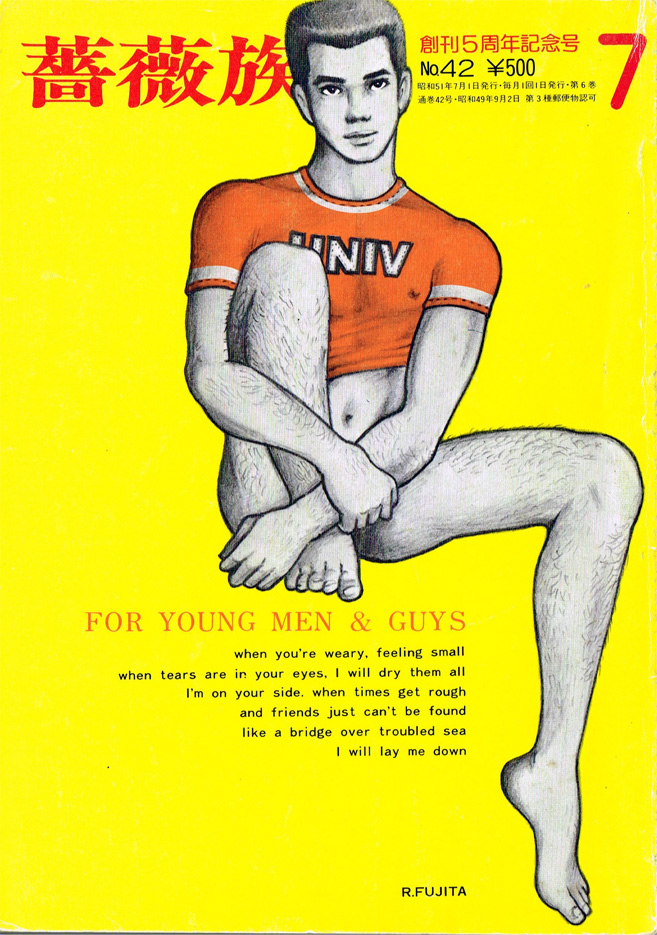

Barazoku

Barazoku (薔薇族), meaning “rose tribe”, was the first Japanese gay men’s monthly magazine first circulated in July 1971 by Bungaku Itō. Gay manga were part of Bara-Komi, a 1986 supplemental issue of the overall magazine.

Some male artists gave their contributions here and their depiction of men was not as exaggerated or sharp as it is now. They include: Rune Naito and Go Mishima. Rune’s style was noted for his kawaii-aesthetic where he draws large heads and baby-faced features. In his works, the men were not as explicit in showing off skin as he emphasized on the sexiness aspect of it. He does have a point in the tease is better than outright exposing everything. What is similar here, the body shapes resemble what you see in bishounen males, just without the body hair. Of course, not everyone can agree with his style. And here comes Go.

Go’s style is leans more on the macho side of men, sometimes including Yakuza-inspired irezumi tattoos. He also has a fascination of the male crew cut hairstyle. At one point in his life he met Yukio and was encouraged by his enthusiasm in creating homoerotic art. His name was a pen name for honoring Yukio Mishima’s death and after contributing to Barazoku, he founded another gay magazine named Sabu in 1974.

If I were to choose which style in the early years, I would prefer Go’s style. Why? Just look at it. (NSFW image) He doesn’t hold back in his works and you can feel the rugged edges around the subject. I could go on and on thirsting for his works and there are contemporary artists who do the same.

The magazine was in print for a span of 37 years until its cease in publication on 2008. There were attempts to revive the magazine in 2005 and 2007 yet it experienced financial difficulties with the existence of the Internet and the decline of print media.

Fuzokukitan (1960-1974)

There’s limited information about this magazine due to little to no translations as it also influenced Bara. According to Gengoroh Tagame, the magazine included straight, lesbian, and gay content with its own fetishes all-in-one. Basically one genre influenced the other. Along with Barazoku, Bungaku Itō coined the term Yurizoku (百合族), meaning “lily tribe”, to describe lesbian content.

Contemporary Gay Japanese Magazines

While Barazoku had a long run, more magazines proliferated as it grew and focused more on topics not covered in Barazoku such as gay pride, HIV/AIDS, club culture, and specific fetishes like salarymen. Even modern gay manga became more explicit as a result of continuous oppression through the years.

One magazine targeting on the specific fetishes was Samson (1982). It includes daddies, older chubby men, and salarymen in suits or men wearing loincloths only. The more recent magazines in the market were Badi (1994) by Terra Publications and G-men (1995) by Furukawa Shobu.

Most of G-men’s magazine covers were drawn by Gengoroh Tagame, and it strived to have running serialized manga, as how manga publishing companies do today. It catered to gay men who prefer more muscles (and hair) over the sleeker yaoi style. Manga with bara characters were limited to one-shot stories in other gay magazines to minimize losses. Yet despite efforts, its publisher stopped continuing its print lineup in February 2016 and continued in different ventures online futhering the difficulty of consuming gay media.

Badi magazine focuses on modern-day gay Japanese lifestyle. If you wanted to know where are the go-to gay-friendly places from restaurants, spas, and brothels. There’s also some health tips, fashion trends, upcoming events, and some gay manga on the side. But it also got the short end of the stick where its final issue was published last March 2019. And I’m not joking. It’s not that far from where we are now if you think about it.

As the decline in print media arises, some Japanese gay magazines try to stay on foot even with the rapid developments. Some either became bankrupt or continued their services online exclusively. However, the internet thrives on content of any kind and will find a way to distribute through other means, as long as you know where to find them. Like porn, it can be distributed freely and no one would complain.

Current State of Bara

Right now bara or gay media is floating somewhere in the sea of information with an added language barrier or not. The word became an umbrella term for all kinds of Japanese and non-Japanese media featuring masculine men, furries, fan art, and more. In the case for gay manga, creators start out through doujinshis to test the waters. The only way left to find them is searching them on your own even if it may mean finding it someplace else.

One thing to note: the term isn’t used extensively in Japan due to its demeaning origins. So they either use the terms Gei komi (ゲイコミ) or Gei (ゲイ) instead. Do not confuse this with BL because it is another genre of its own.

Luckily, a collection of gay manga through the years translated in English is compiled in Massive: Gay Erotic Manga and the Men Who Make It. Works from current gay manga artists are included and it is a fraction of what the genre stood in time. If there is a publishing company who’s willing to publish explicit and wholesome bara manga I will gladly put it on my shelf.

Pride Month 2020

Related Articles to Read:

- BA-RA-KEI: ORDEAL BY ROSES, BY EIKOH HOSOE

- Japan’s first magazine, and the first in Asia, dedicated to gay men, Barazoku, was launched in 1971

- Goh Mishima biography

- ‘Massive: Gay Erotic Manga And The Men Who Make It,’ Chronicles Gay Japanese Manga

This was an interesting read, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked it! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] The Origins of Bara […]

LikeLike

Very interesting. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I had a good time researching what I could find.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] The Origins of Bara […]

LikeLike